Protection Against Ambient Air Pollution

When Cindy Tu arrived in Saigon last December, she looked forward to taking that first ride through the city’s buzzing traffic. Until, of course, she got behind a Saigon bus.

“I couldn’t handle it,” says the San Francisco native. “Because I’m so sensitive to smell firstly but I’m not used to the pollution. I started wearing those medical disposable face masks, which did nothing for me. I ended up layering like three of them… then I moved on to the cloth kind that they have. That didn’t do anything for me, either. Honestly, I started getting respiratory problems and I was coughing a lot and I just felt really sick. I thought: ‘This is ridiculous.’”

In no time at all, Tu found herself seeking new ways to deal with Saigon’s ever-increasing air pollution. But while it’s easy to acknowledge that our city’s air is unclean, solutions seem to be few and far between. Eventually, Tu came across Vogmask, a line of practical, fashion-forward face masks, on a trip to Singapore. She now swears by them and has begun distributing for the brand in Vietnam.

“It’s a good investment,” says Tu. “I use it every day for two months and it makes a world of difference. Now I feel like, you know, let’s go on that ride because I’ve got my Vogmask. Because [if] I went just with nothing, no way.”

This doesn’t necessarily solve the city’s pollution problem, but Tu’s masks have made it all the way to Hanoi and around the country, helping urban residents shield themselves from airborne particles and debris. Given the fact that one quarter of the global population now breathes unsafe air, according to the findings of Yale University’s 2014 Environmental Performance Index, there’s certainly a market for this kind of protection.

In Saigon and around the world, polluted air contains two kinds of particulate matter. PM10, the larger of the two, includes all particles less than 10 micrometres in diameter and can accumulate in your lungs over time. But the real culprit is PM2.5, better known as fine particulate matter, which is about 1/30 the width of a human hair and so small that it’s able to make its way deep into a person’s lungs, causing a whole host of medical conditions, from chronic respiratory infections to heart attacks, stroke and lung cancer. In 2012, the World Health Organisation (WHO) counted 3.7 million premature deaths worldwide related to ambient air pollution, nearly a million of which were in Southeast Asia alone.

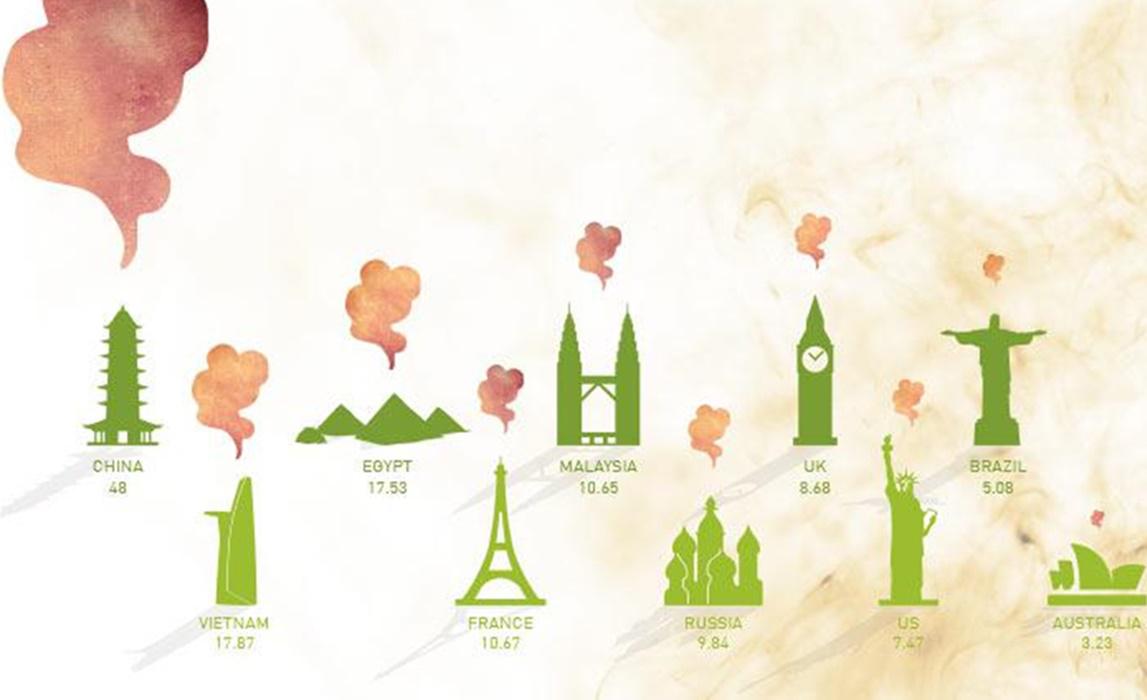

So, how dangerous is the air we breathe? According to the WHO, safe air contains an average of no more than 10 micrograms of fine PM2.5 particulate matter per cubic metre (µg/m3) per year. While Saigon may not be as bad as Beijing (56µg/m3), Hong Kong (45µg/m3) or even Hanoi (39µg/m3), our annual average is 27µg/m3, or nearly three times the acceptable rate.

As Dr Jonathan Halevy, a pediatrician at District 1’s Family Medical Practice, says: “If you live in Ho Chi Minh City and you don’t cough, something is wrong with you.”

Over the last 10 years, Dr Halevy has seen a marked uptick in the number of patients who come to his office with pollution-related conditions. While ambient air pollution is dangerous for adults, children are even more at risk: kids living in polluted areas are more likely to develop asthma, he explains, as well as sinus problems, respiratory conditions and even skin diseases like eczema and atopic dermatitis.

“It just gets worse and worse and worse,” he says. “Kids that have asthma, their asthma becomes more and more difficult to treat. It becomes more chronic [and] less responsive to treatment because they’re continuously exposed to pollution, especially kids who live near highways, kids who live near construction sites. There’s a construction site almost in every neighbourhood in Vietnam, so you can’t escape it.”

However, while there’s an obvious risk in the city, Dr Halevy acknowledges that finding a solution to the problem is no easy feat.

“At the moment, the only way to solve this problem is to get rid of the traffic and that’s impossible so you either live with it or you go away,” he says.

For individuals, something as omnipresent as air is difficult to control, however it is possible to avoid being outdoors at certain times of day, like rush hour, when air pollution is at its worst. Across the city, motorbike riders and walkers alike have adopted the habit of wearing a face mask, which some – Dr Halevy included – are skeptical to endorse, as there is limited scientific data on the effectiveness of these masks against PM2.5.

That said, a 2012 study published in US-based journal Environmental Health Perspectives found that use of a face mask can help to reduce the adverse effects of air pollution and lower the associated risks of cardiovascular disease. Conducted in Beijing, the study tracked mask wearers with a history of cardiovascular disease while walking along the city’s heavily polluted Second Ring Road. When the masks were on, patients experience lower blood pressure and improved heart rate variability as well as a self-reported reduction in symptoms and perceived exertion.

Though it depends largely upon the face mask you choose, there are some who endorse face masks as a way to protect against harmful airborne pollutants. Dr Richard Saint Cyr, a US-certified family physician, blogger at MyHealthBeijing.com and occasional health columnist for The New York Times’ China edition, has written and researched extensively on the effectiveness of a variety of face masks in Beijing’s urban areas, where he lives.

By Dr Saint Cyr’s assessment, the answer to pollution protection lies not in the local market or the pharmacy but at the hardware store. Dr Saint Cyr refers to 3M particulate respirator masks – often used by construction workers and painters – as the “gold standard”. Cheap, disposable and lightweight, these may not look much different than the flimsy surgical masks worn by many local residents but include a proper filter, fit better on a user’s face and are certified by the United States’ National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH). Best of all, they can be found at many of the hardware stores located around District 1’s Yersin Market and cost VND 10,000 apiece.

The only downside to a 3M mask is that you’ll look like a construction worker. As far as fashionable masks go, San Francisco-based Vogmask provides adequate protection as well as an array of colourful designs. Though they’re more expensive – your average Vogmask goes for just over VND 500,000 apiece, though it can last you up to five months, depending upon frequency of use – these microfibre masks are also effective in blocking out pollution thanks to the carbon filter inside and come with the added comfort of one or two exhalation valves. In fact, Vogmask graced the runway at Hong Kong Fashion Week last year, making it one of the only consumer-focused masks that hasn’t sacrificed function over fashion.

Whatever you choose, there are a few important things to take into consideration when buying a face mask. First, keep an eye out for masks which are certified by international standards. 3M masks, for instance, bear an N95 certification from NIOSH, meaning that they are proven to block at least 95 percent of airborne particles. If you’re unsure of whether or not a mask is actually NIOSH-certified, the organisation keeps a public list of certified products on its website. While Vogmask doesn’t appear on this list, Dr Saint Cyr ran his own Fit Factor tests on a host of face masks last year, including Vogmask. The results were positive, with Vogmask blocking out 95 percent of particles, though he acknowledges that there is no one-mask-fits-all solution.

Second, no matter the quality, an ill-fitting mask allows polluted air into the mask, reducing its efficiency. Look out for features like adjustable straps or a metal nosepiece that conforms to your face. To ensure that a mask fits well, eyeglass wearers can do a simple test: put on your mask and exhale. If your glasses fog up, air can get out of – and into – the mask.

Finally, comfort is important, particularly for those who spend long bouts of time on a motorbike. Additional features like an exhalation valve can help to make breathing easier for mask wearers and may even reduce the amount of air leakage around a mask. Straps that go over your head – rather than just around your ears – are often more effective, however some might find that ear loops are more comfortable.

While it’s safe to say there’s no overarching solution coming to Saigon anytime soon, face masks may afford users at least some protection against outdoor pollution. According to Dr Saint Cyr, these can be worn for up to a week, depending upon the levels of pollution to which you’re exposed. You’ll know when it’s time to switch masks, as breathing will become difficult when the filter is maxed out.

Dr. Jonathan Halevy - Head of Pediatrics, Family Medical Practice Ho Chi Minh City

We use cookies on this website to enhance your user experience

We use cookies on this website to enhance your user experience